As mentioned before, I have recently become study and student of Mark Brahmin’s Roman Interpretation, a system of reading made necessary following his theory of Esoteric Moralisation. His work seeks to expose and decipher the system wherein esoteric messages have been purposefully woven into Art and Religion for millennia in order to moralise an in-group and demoralise an out-group. His project is mostly concerned with ancient and modern cultural expressions, be they sacred text or popular cinema — all of this he terms Art.

My interest is in, specifically, non-hermetic fictional prose and image carefully produced and marketed towards a wide swath of the public; whether men, women, children, or, and this is usually ideal, entire families. These pieces can be termed, in J. R. R. Tolkien’s tradition, fairy stories, or folk tales, or Romantic fantasy, and these are stories which, perhaps most obviously, provide a moral building-block for children. Further, these stories are understood by the public to arrive, and have historically arrived, organically out of a common spirit. They are, accordingly, thought to represent the people who tell them, but the writers or compilers have often done much more than this — Roald Dahl, for instance, of course, consciously placed morals into his stories knowing that they would affect or instruct the morals of the readers. Ergo, folk tales were a perfect vessel for unconscious esoteric messaging, and thus have certainly been used in the demoralisation, or self-effacing, of Europeans.

In order to properly direct these tales, we must develop Folk-Art, which will be an apparatus or methodology for creating such types of art which consciously uplifts and glorifies Europeans. This will always utilise Racial Esoteric Moralisation. In essence, it is a form of Myth which can be circulated popularly and told to all, including children, in the modern day.

(EDIT: Myth is perfect representation and education, and all Art perhaps budded as such — as paintings on walls to assist in the gathering of food, as a fellow traveler intimates here. We are treading very comfortable ground in attempting to instil information and values through myth.)

This requires Folk-Art to be accessible, but also to uphold the values that we wish to inform our people about. It need not be violent, nor utilise violent themes, but it must essentially and seriously evaluate and inform about violence. It need not be antagonistic, though it must be conscious of our antagonism to modern values, and to specific forces within the world. It need not be antiquated, but its values are allowed to be perceived as such, as we may utilise perennial stories.

(As an aside, it should be understood what I mean when I say “violence.” In the terms of transgression, of assertion, of Nietzsche’s agon — I talk of violence as consisting of two perpetrators and no victims. It is not directed violence, it is not a call to violence, and it is not praise of violent acts: it is only the will to engage. In this we will be distanced from modernity’s moralism, which is ruled by what the market needs, or “peace.” For fear of misunderstanding, I speak plainly: even symbolic violence, or a mode of thinking in which we are not averse to violence, serves to distinguish us — I do not advocate lawless violence.)

Indeed, effecting meaningful caution, here, will be worthwhile. As many in our movement are, we must represent and emphasise our idealism: minds will change, and then the world will change. This is not meaningless abstraction: again, when we rise to the challenge, we will control consciousness, and the same way that much of modern and contemporary Art has been made specifically to damage us; with sophistication, aesthetics, symbols and care, we will make it uplifting — our production will finally be consciously moralising.

For ease, these folktales will often take on familiar patterns or storylines, utilise well-known character archetypes, or reinforce morals which, until the most recent turning of the wheel of modernity, were mainstream. For this we can consciously, not blindly, deploy phylogenetic readings of the Aarne-Thompson-Uther classification system of folklore narratives. This refers to the phenomenon that some stories emerge more commonly amongst certain groups of people, or, put another way, that some narratives resonate especially with certain Europeans.

While a metastudy of folklore would be beyond my singular ability, though perhaps in the future will become necessary, my own research towards creating Folk-Art will include examining specific stories. I will give examples of how these stories could be amended to suit us while simultaneously preparing a full piece of work which satisfies the above and remains publishable.

Our Folk-Art, put simply, as Myth being utilised in the realisation of our Religion, must be salubrious, it must be moralising to our race, and this must be done consciously. From amongst a healthy people, uplifting stories will perhaps naturally occur, but we do not live within healthy societies, and our people have been made unhealthy. Further, we have adversaries who employ these tactics consciously, and have before taken advantage of our witlessness — we do not have the luxury of awaiting organic stories.

To ensure I have the obligatory Nietzsche reference: he agnised that the “common-currency humans” of the present require something to pursue, and that myth can uplift, as well as unite, us. Folk-Art, then, with so much fluff, will be motivation. It will be the next step in awakening that we need, where other struggles are ongoing, we can push through modernity by enacting a different type of personal revolution: to create in us the Super-human, while ensuring that it is also supranational.

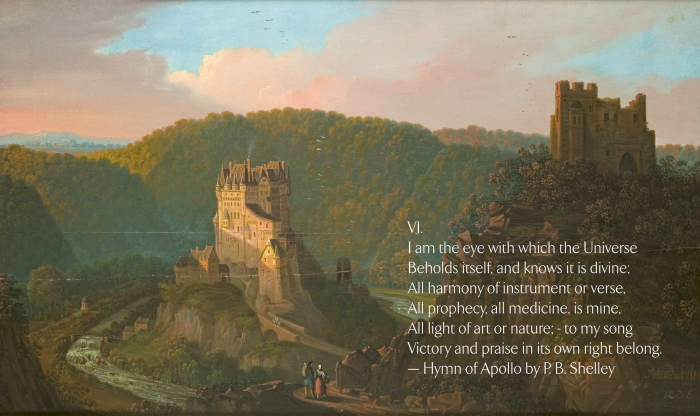

Our Folk-Art cannot contain messages hidden to us. It is with pride, caution, respect and perhaps lamentation that we must evaluate and edit these stories to better fit our agenda, to better represent our people, and to glorify our Apollo. This is the insertion of esoteric messaging, acting as the Syrian scribe who found the Osirian temple-chant and turned it into the Song of Solomon. T. S. Eliot wrote that “the romantic Englishman is in a bad way,” but this only gives us an excuse to begin again, and to flood all mediums with our Art, our Myth — our Religion.

We must produce paeans; hymns chanted to avert evil; warlike songs. Through us, our Art will be made Noble again. Ave Millenarium.

Love it. Can’t wait to see more. We must develop artists deploying a shared symbol language.

LikeLiked by 1 person